"Architecture is the thoughtful making of spaces," said architect Louis I. Kahn. "It is the creating of spaces that evoke a feeling of appropriate use."

Kahn was commissioned in 1959 to design a new building for the First Unitarian Church of Rochester, New York. The congregation had met for many years in a building of special architectural quality, designed in 1859 by Richard Upjohn, a leading 19th century architect and founder of the American Institute of Architects. When that building had to be demolished for downtown redevelopment, the congregation felt a responsibility to replace it with one by a leading 20th century architect, giving the community a notable example of contemporary architecture.

A search committee interviewed a number of nationally known architects and recommended Kahn. Those who interviewed him felt that he was instinctively close to Unitarian Universalist ideas as well as an innovative architectural leader. His aesthetic philosophy was expressed in terms close to mysticism, words struggling to communicate a complex creative process. His intuitive architectural solutions began with a concern for the integrity of materials, a feeling for the expression of structure, and a desire to return to essentials, to express "only what matters."

In designing the First Unitarian Church of Rochester, Kahn began with a simple concept sketch. As he faced the initial congregational meeting, he drew on the blackboard, as he later explained, "my first reaction to what may be a direction in the building of a Unitarian Church. Having heard the minister give a sense of the Unitarian aspirations, it occurred to me that the sanctuary is merely the center of questions and that the school was that which raised the question and I felt that that which raised the question and that which was the sense of the question - the spirit of the question - were inseparable."

Kahn's concept sketch began with a question mark, chosen to represent the sanctuary, at the center of the building, surrounded by a circle to serve as an ambulatory representing the shades of belief possible in a Unitarian congregation. "I drew the ambulatory to respect the fact that what is being said or what is felt in the sanctuary was not necessarily something you have to participate in."

Next the sketch showed a corridor to serve the church and "the school which was really the walls of the entire area, so the school became the walls which surround the question."

"I felt that a direct, almost primitive statement was the way to begin, rather than a statement that already had many expressions of experience" and so he set down a drawing of what he felt "presented the inseparable parts of what you may call a Unitarian place."

This simple drawing represented the basic idea of a possible Unitarian church, its theoretical components in the architect's thinking.

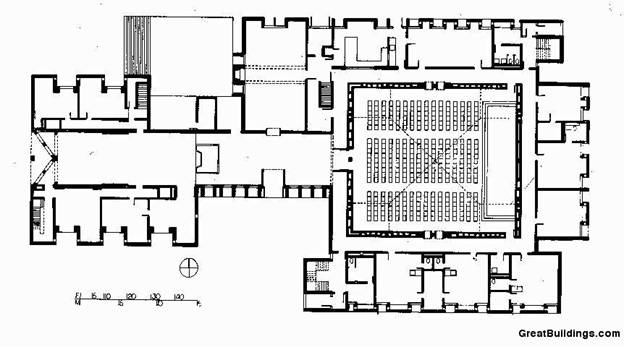

In translating this basic idea into a building, Kahn worked with the congregation's building committee in a long design process, ending finally with a floor plan in which can be traced some elements of his first concept sketch. The sanctuary is at the center of the building, surrounded by a corridor and then by the school. The center of the question is surrounded by the spaces for learning. A later addition giving more spaces for offices and classrooms extends the building to the east.

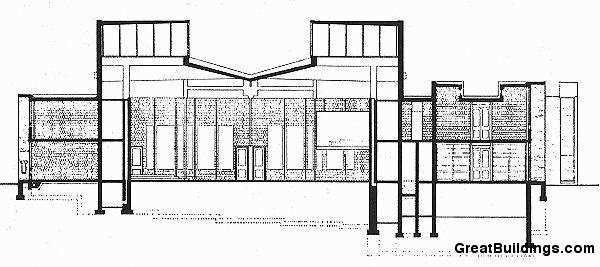

Making the sanctuary central

presented the architect with a practical problem: how to bring natural light into a totally

enclosed space. Kahn felt strongly about light: "All spaces need natural

light. That is because the moods which are created by the time of day and

seasons of the year are constantly helping you in evoking what a space can be

if it has natural light and can't be if it doesn't. Artificial light is a

single tiny static moment in light and can never equal the nuances of mood

created by the time of day and the wonder of the seasons."

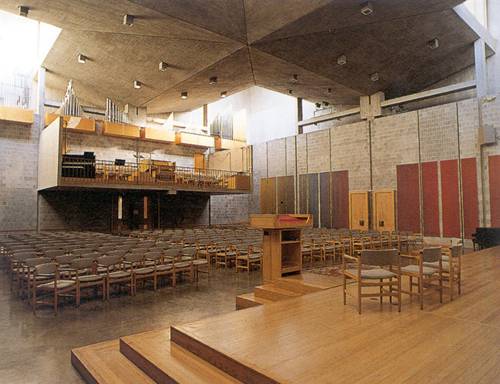

For the Unitarian Church, natural light

floods in through four towers piercing the corners of the central room. The

changing light of the seasons and the days fills the room "like a silver

chalice," as one author has said.

Bringing natural light to the outside

rooms, the walls of the school, presented another problem. Kahn said that he

"felt the starkness of light, learning to be conscious of glare." So

the windows are protected, set in deep masonry reveals. Each room on the lower

floor of the main building has a side-lighted window seat set between two large

glass areas.

The building committee suggested window seats, particularly for the classrooms for smaller children, and Kahn welcomed the thought, feeling that "it adds a friendliness, a note of comfort and a kind of getting away from someone and being alone even in a room where many are present."

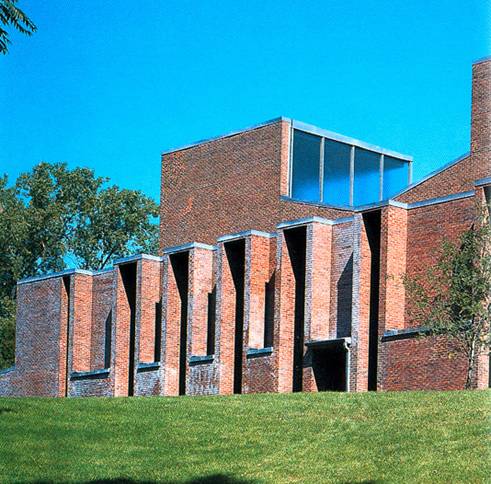

The framing for these deep protected windows and for the seats they enclose give the exterior walls their strongly varied massing. The elevation for each side of the building differs as the rooms inside differ, reflecting each room's function in the shape of the exterior wall.

Kahn believed in the integrity of materials. In the First Unitarian Church, he used materials which did not need to be given an additional finish: brick, exposed wood, concrete block, and poured concrete.

The main exterior surface, brick, was carefully selected for its texture and color. Masons working on the brick walls were asked to undercut the mortar joints with a pointed tool while the mortar was still soft, emphasizing the importance and weight of each individual brick. The same method of careful detailing was employed in laying the selected concrete block.

In areas to be covered by poured concrete, which he called "liquid stone," Kahn considered carefully the fact that the hardened concrete surface would inevitably bear the impression of the wooden forms used to receive the liquid material. He specified that large wall and ceiling areas would be poured in forms made of fir flooring, to give the texture and pattern of thin wood strips to the final surface. These large panels of wooden forms had to be held parallel by metal screw-ties until the concrete hardened. The holes left behind by these screw-ties make a natural pattern that marks all the broad interior surfaces.

On the other hand, when concrete was used for a large beam, a single long form was used so that there would be no apparent break in a strong supporting member.

Because the general effect is one of simplicity, small details have been handled with great care. Paradoxically, effective simplicity is difficult to achieve. Many faults can be hidden when a wall is covered with applied ornament. When a wall is broken only by functional openings, the effect of the design depends upon their careful placement. On the interior walls of the sanctuary, the only breaks are functional. The concrete block of each wall parts to show its "bones," the long concrete pillars that support the roof. The side walls are broken also by long slits through which heat is circulated.

Woven hangings spaced on the side walls were designed by Kahn and woven by Jack Lenor Larsen. In them, the three primary colors mingle to create a spectrum. The large central room, which serves as sanctuary, auditorium, and multi-purpose room, is quiet and cool when it is empty. It comes to life as a container for human activity, a welcoming receptacle for people.

Doors of white oak, offset from the concrete walls, call attention to the entrances of the central room. The main doors enter under a cantilevered choir loft, giving a sense of enclosure that is released when you leave that shelter and feel the roof soar over your head.

The organ was originally built for Rochester's St. Bernard's Seminary by the Wicks Organ Company, Highland IL, in 1964. During the summer and fall months of 1981, church members purchased and moved the instrument from the seminary to this sanctuary. It was revoiced and expanded to 16 ranks and four extensions by the Kerner and Merchant Organ Company of Syracuse NY. The instrument, dedicated on November 1, 1981, is made up of 1095 pipes and has two-manual and pedal direct electric action.

In the southeast corner of the original building is the lower lounge, named for Susan B. Anthony, for 50 years a member of the congregation. It is furnished for small meetings and informal gatherings. The room takes warmth from a ceiling of wood strips and a fireplace. On the second floor, the same southeast corner holds a room of similar shape designed as a chapel for the church school, now used as the Choir Room. Like the worship space in the main sanctuary, this room has light streaming from high windows. Here too a fireplace stresses the opportunities for warmth and companionship.

In 1967, when the original building had proved so successful that it was overcrowded, the congregation decided to expand the building. Kahn was asked to design an addition, giving additional space for both adult and school activities. Kahn's reaction was to remind the congregation that the new section would be similar but not identical, since both he and the church had changed in the intervening years.

The first floor of the new addition centers on an open gallery which can be an extension of the lobby or closed off by massive doors for small meetings or services. Offices for church staff and ministers parallel the gallery. A fireplace emphasizes the theme of warmth and fellowship.

On the second floor, the new addition holds a cluster classroom, a loose arrangement of spaces which can be thrown together of temporarily separated for a variety of church activities. Once again, a fireplace is an essential element, with a hearth bordered by light wells to bring natural light into the focal point of the room.

Both central areas of the new addition end in large complex windows, giving each room a sense of the natural world outside.

The site of the church is near Rochester's expressway and Outer Loop system, making it available to a congregation which comes from all areas of the local community. A simple brick sign on Winton Road indicates the entrance for cars, leading to the adjacent parking area. http://www.rochesterunitarian.org/Building_desc.html

http://www.rochesterunitarian.org/Building_desc.html